Did you know that up to two thirds of older patients will experience delirium when they become ill?

Delirium is an acute confusional state that occurs because of an underlying physiological problem such as illness or injury. Symptoms of delirium differ from person to person, including memory problems, hallucinations, issues connecting to their surroundings and changes in sleep patterns. However, the key symptom of delirium is difficulty concentrating, also known as inattention.

Despite a focus on delirium in the past few years, the rates of this condition are not improving. This medical emergency is linked to increased risk of dementia, death, hospital stays, long-term care home placements, and patient and caregiver distress. It can also lead to decreased quality of life for patients.

Many researchers have studied screening tools for recognizing delirium. One of the biggest challenges is findings ways for health care practitioners to implement these tools into regular practice. Through hospital-based research at Lawson Health Research Institute, Dr. Niamh O’Regan is tackling this problem.

Last year, Dr. O’Regan, Lawson Scientist, developed and implemented a delirium screening algorithm on the Acute Elderly Care (ACE) Unit at London Health Sciences Centre’s (LHSC) Victoria Hospital. Nursing staff and students were trained to use two tests: Recognizing Acute Delirium As part of your Routine (RADAR) and Months of the Year Backwards (MOTYB). For RADAR, nurses observe patients when they check vital signs like temperature and blood pressure. They also ask patients to say the months of the year backwards to test their concentration, which is usually affected by delirium. Dr. O’Regan and team studied the feasibility of implementation of this screening method, as well as patient, caregiver and nursing satisfaction.

Results showed that training was highly effective and that screening took, on average, 70 seconds to complete, less than many other screening tests. Data on the effectiveness of the screening in detecting delirium is currently being analyzed.

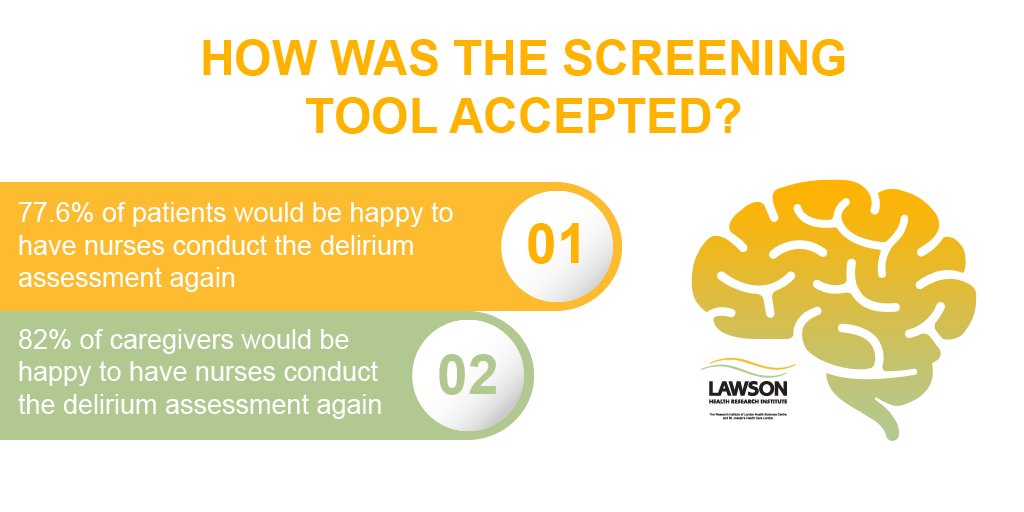

The research team also studied acceptability among patients and caregivers by having them complete a survey. The results showed patients and caregivers had very positive feedback with many agreeing they would be happy to have the daily screening conducted if admitted to hospital again.

The results showed positive feedback from patients and caregivers.

“Developing good delirium practices is possible, but requires collaboration with researchers, clinicians, hospital management, patients and families.” says Dr. O’Regan, a consulting geriatrician at LHSC.

Researchers stressed the importance of collaboration throughout the study. In training, they had open discussions with nursing staff to better understand the barriers to recognizing signs of delirium. The research team also used feedback from the staff to adjust the research tools to best fit into their routine.

“It was important for us to understand how well the screening tool fit into the nurses’ working routine. We also wanted to know if it was acceptable to staff, patients and caregivers,” adds Dr. O’Regan. “Many studies have examined the accuracy of screening tools in detecting delirium, but often don’t examine how well the tests work when applied by front-line staff or the ease of implementing them in busy clinical units.”

Today, the research team is exploring the experiences of the nursing staff in using the tool. Nurses have filled out an anonymous online survey with their feedback, and researchers are in the process of conducting face-to-face interviews to learn more about their experiences in using the screening tool, as well as barriers to implementation and suggestions for improvements.

The ultimate goal is to embed a version of this screening tool into regular practice on the ACE unit, while expanding this initiative to other clinical areas where patients are at high-risk of developing delirium.

“For physicians, thinking about whom you’re dealing with and the person behind the delirium is very important in care,” notes Dr. O’Regan. “When a patient is confused, you need to firstly ask whether this confusion is part of the patient’s normal state or whether it’s new or worsened. If it’s new or worse than usual, delirium is likely and searching for a cause, as well as modifiable risk factors, is critical.”

Dr. O’Regan adds “as well as addressing the underlying cause, there are many other interventions recommended to help that patient. Engaging family, regular reorientation and reassurance, and early mobilization are only a few examples. Knowing a patient’s personal history can also help by offering conversation topics and giving ideas about how to engage the patient in activities that may cognitively stimulate or reduce agitation.”

Dr. O’Regan stresses the importance of learning about delirium. This is why she is a part of the third annual World Delirium Awareness Day taking place on March 13. Last year, she and an inter-professional team at London Health Sciences Centre developed videos answering frequently asked questions about delirium that are now used worldwide. This year, she’s helped developed a quiz called “What kind of delirium superhero are you?”, and encourages people to complete the quiz on the iDelirium website.

People wanting to engage on social media can use the hashtags #WDAD2019 and #deliriumready. More information about delirium and the international day can be found on iDelirium’s website.

This study received funding from the AMOSO Opportunity Grant and the Margaret Banks Fellowship.